100 Objects (Prologue)

“When you realize there is nothing lacking, the whole world belongs to you.” - Lao Tzu

Museums bore me. This is a shock as I used to love museums. Natural history, science, aerospace, and art museums. Aquariums, roadside attractions, blue-chip and no-chip galleries, cabinets of curiosities. Halls and corridors of oil paintings, geological treasures, archaic instruments of medicine and music, costumes of war and dance. I have even helped build museums of casual objects, psychphonics, and nursing history for a public hospital. Why this sudden change, this aversion to them as if it is a chore or obligation? And don’t even get me started on public art and monuments in their fajita-like grandeur. You know, the look-at-me stone, bronze, and plinthed significance, like an obnoxious sizzling dish served up, impossible to ignore.

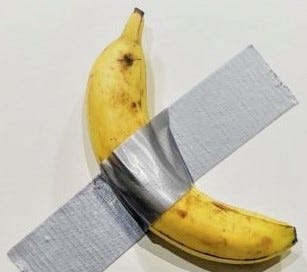

And art? Yeah, over it. The politics, the money, the power, and the illusion of value propped up by vast operations of proclamations and auction houses. A banana duct taped to the wall and then eaten by a cryptobro in the lobby of a luxury hotel. Local drama and egos, my own included, have also soured it for me. I have adopted a theory of culture not too dissimilar to Pierre Bourdieu's, which Ben Merriman details as such: “Bourdieu argues that variations in taste, and the success of the powerful in making their personal tastes appear to be natural or objectively valid, play a role in reproducing large structures of social inequality.” I have become no fun to be around, and this is my attempt to change that, to remember why I loved art and museums and objects in the first place.

I recently read Jerry Saltz's book Art is Life (2022). In it, Jerry just looks and appreciates what he sees, avoiding the paralysis that could come from investigating the complex interplay of resistance and reliance on the art market to create and present the objects he is observing. While contextualizing the work of art socially, culturally, and politically, what resonated with me was his reflections on how the art makes him feel. He reflects the feelings, memories, and ideas evoked. His joy in looking convicted me of my cynicism. I want to look and see the world again with similar patience, playfulness, and gratitude.

In previous essays, I explored getting rid of everything, working towards evaporation, and detaching from the trappings of consumption and materialism. This now is another form of me getting rid of everything by realizing, in the words of Lao Tzu above, that everything is mine. Everything is also yours. Now, when I walk into a museum, I am grateful they are keeping all of my stuff safe—my pterodactyl, my Van Gogh, my moon rock, my mummified pharaoh.

I recently spoke to a middle school class about film scores (during the Q&A, one kid asked if I had a dog). They had an assignment to script and produce a 45-second video. I concluded my presentation by instructing them to make something awesome and make something only they could make. I am giving myself the same assignment. By awesome, in the truest sense of its etymology – wonder-filled. I want to be amazed again, like when I first learned about glow worms, Andy Kaufman, the taste of yuzu, Alice Coltrane, breakdancing, Pee Wee Herman, Incan civilization, the Oregon coast, the light and space art movement.

I want to experience new things for the first time and maybe rediscover an old thing or two. I want to find wonder in that wander, the possibility of a transcendence that returns me to where I already am. I want to be surprised by the beauty of things I have and have yet to discover and the joys of things I have and have yet to see, taste, and hear. I want to end with more questions than answers. I want to unsatisfy my curiosity.